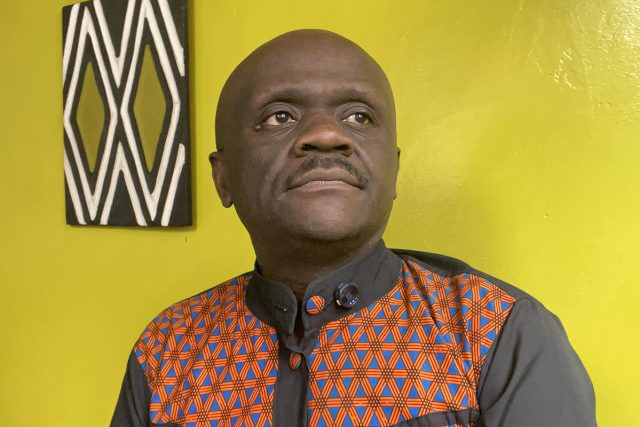

History, when written well, doesn’t sit quietly on a shelf. It stirs. It whispers. It insists that the reader lean in, listen, and ask: What now? That is the sensation of reading Savannah Footprints: Wisdom Whispers from Historic African Leaders by DJ Bwakali. It is not merely a book; it is a conversation across time, a dialogue with African leaders whose words and deeds refuse to be confined to dusty archives.

Bwakali doesn’t tell history; he breathes it. He summons figures like Murtala Mohamed, the Nigerian general whose brief but blazing rule challenged corruption, or Samori Touré, the West African emperor who refused to bend to French colonial conquest. They don’t appear here as names in textbooks, but as living presences, men whose choices still echo in the heat of today’s African debates on sovereignty, governance, and identity. You don’t read them; you meet them.

The prose is alive with the cadence of the savannah itself: spacious, rhythmic, sometimes harsh, always luminous. Each chapter unfolds like a story whispered by a fire in the dark, pulling the reader into moments of defiance, betrayal, triumph, and loss. Yet Bwakali never lets nostalgia weigh down his storytelling. The real power of Savannah Footprints lies in its double vision: the past is always a mirror held up to the present.

Africa’s history here is not embalmed. It is weaponized. The struggles of yesterday become blueprints for tomorrow. When Bwakali recounts the courage of leaders who dared to imagine Africa free, he is not simply chronicling their resistance; he is reminding us that Africa today, with its contested elections and unfinished revolutions, is still standing at the very crossroads they once stood upon. To read this book is to be haunted by the possibility that the answers we seek for Africa’s future have already been given, if only we are willing to listen.

But what makes this work essential is not only its moral urgency; it is its accessibility. Bwakali writes with clarity, but also with intimacy, weaving the scholarly and the lyrical. He does what few historians dare: he collapses the space between academic rigor and emotional truth. The effect is a book that belongs as much in university classrooms as it does in the hands of young Africans searching for role models, or policymakers searching for vision.

In a time when Africa is often narrated from outside, Savannah Footprints feels like reclamation. It tells Africa’s story not as tragedy, not as footnote, but as prophecy. For those who wish to understand Africa, not only where it has been but where it insists on going, this book is not optional. It is essential.

Bwakali has given us more than a history book. He has given us a lantern. And in its glow, the past and future of Africa walk side by side.